Until recently, when the word “Barbosa” was pronounced in the world of football, the memory recovered almost exclusively related the athlete to the 1950 World Cup. Precisely, the Brazilian defeat to the Uruguayans in the quadrangular final of this sports competition, which took place not only in Brazil, but in the heart of the Maracanã Stadium, crowded by about 200 thousand people. It is a non-spontaneous mnemonic process, the result of a social construction of the memory about the “16th of July”, which still attributes to Moacyr the nickname “goalkeeper of Maracanazo”.

The “invention” of this story took place by certain agents, especially sports directors, journalists and intellectuals, not coincidentally white, whose speeches, chronicles and narratives became places of memory. In this representation of the past, Barbosa became a central figure in this national “tragedy” and “trauma”. Everything that the goalkeeper had done in his professional career and personal life was erased to consider him only through this prism, reducing his existence to the “failure of 50” and imputing a guilt he never had.

Within a boastful and interpretive context about Brazil, the result could not be anything other than a racist reading. Over time, even the books dealing with Barbosa’s biographical aspects ended up highlighting in the title the goalkeeper’s relationship with the 1950 World Cup, as can be seen in: Barbosa: um gol faz cinquenta anos, by Roberto Muylaert, and Queimando através de 50, by Bruno Freitas. This was even reproduced in the Rito de Passagem room, in the long-term exhibition at the Football Museum, when Barbosa appeared at the fateful moment of the second Uruguayan goal. In the sequence of the images, the goalkeeper was shown on his knees and with his head down.

The research of the temporary exhibition Time of Reaction — 100 years of goalkeeper Barbosa, which ran between June 2021 and January 2022, therefore had the intention of deconstructing this crystallized memory, offering the public new angles on Moacyr’s trajectory, far beyond the aforementioned world competition, in accordance with anti-racism. Celebrating his centenary meant restoring his successful career and looking for clues about his pre- and post-professional soccer athlete life

If on one hand, therefore, we pursued the traces of the past from its birth in Campinas-SP; on the other hand, in the opposite direction, we pulled the thread of the stories of those who lived with him in his last moments. Where we would arrive was anyone’s guess, especially given the short investigation time and the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, which restricted our circulation and closed institutions in their most severe phase. The paths taken by the research allowed some discoveries, survey of images and the construction of a new narrative about the honoree.

In Campinas-SP, for example, we found some unpublished records about the goalkeeper. His birth certificate allowed us to attest to his official name (without the surname Nascimento reproduced in so many texts written about him), as well as to learn about the place where he came into the world, in the working village of Companhia Mogiana de Estradas de Ferro, the company where his father worked. At Colégio Técnico Bento Quirino, we consulted numerous books until we came across the record of his notes in the carpentry course, which made it possible for us to ensure that he interrupted his training in the middle of 1936, that is, a few months after the death of his father. This fact made him leave his mother’s house and go live with his older sister in São Paulo-SP.

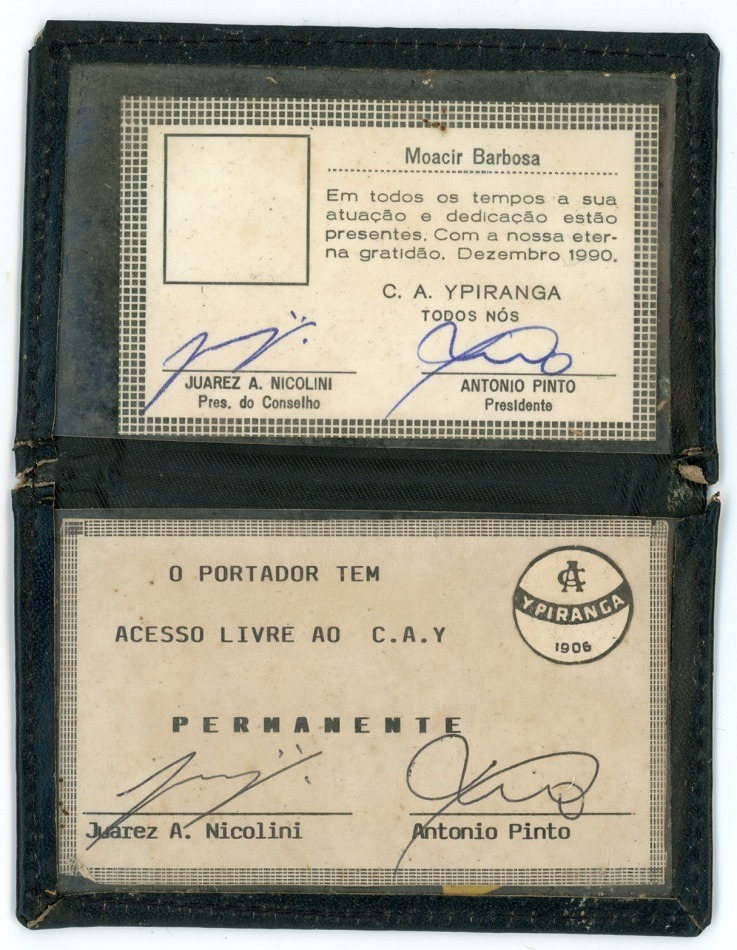

In the capital of São Paulo, in turn, we were able to locate the residence where Barbosa lived and the street where he played naked in his youth in the Liberdade neighborhood. We learned and found records of the history of the Laboratório Paulista de Biologia, the place where he worked and for whose team (LPB) he played amateur championships at the turn of the 1930s to 1940s. And we made not only a visit to Clube Atlético Ypiranga, but we also documented an interview with former president Roberto Nappi, who helped and honored him during his lifetime. In the CAY collection, we saw framed the first contract signed by the goalkeeper as a professional player, dated April 16, 1942.

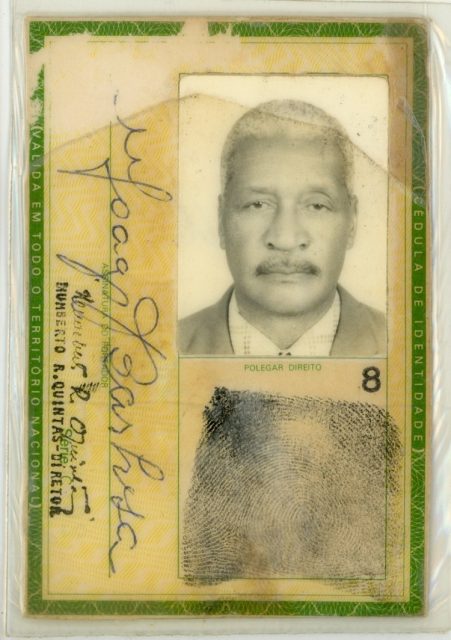

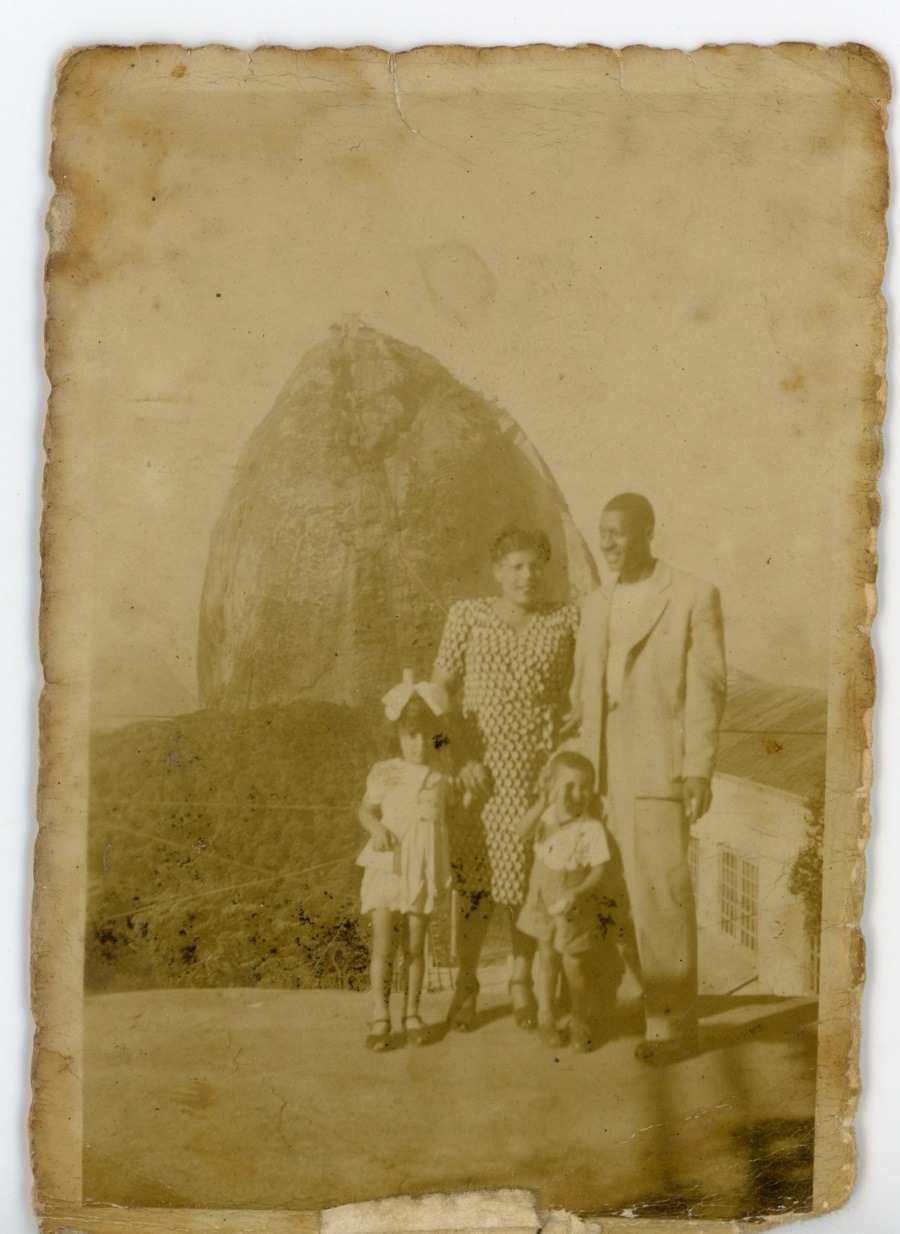

It was in Praia Grande-SP, however, where we had the biggest surprises and discoveries. There we met and interviewed Tereza Borba, Barbosa’s adopted daughter, who lived with him in the last years of his life. In her house, she keeps the goalkeeper’s private collection, including among others: personal documents; more than two hundred photographs, with emphasis on old ones and their private life; gifts and plaques in her honor; replicas of both the medal and his shirt in the Vasco conquest of the South American Club Championship in 1948; an almost life-size statue made of metal; and a sawn piece of wood from Muzambinho-MG, possibly from one of the goals of the Maracanã Stadium in the 1950 World Cup. This particular object was featured in a prominent display case throughout the exhibition. It is not only necessary to give a special thanks, but also to recognize the attention, affection and care given by Tereza. She plays a central role in reconstructing the memory of Barbosa

Throughout the research, more than 50 people from many institutions were contacted and helped to gather sources and information about the goalkeeper. Added to this are newspapers, magazines and photographs collected in many archives and libraries, public and private, with emphasis on: Public Archive of the State of São Paulo, National Archive, National Library and C. R. Vasco da Gama Memory Center. The documents, in general, made it possible to discover layers of Moacyr Barbosa’s public and private life unknown to most people. We call attention to his technical qualities as a goalkeeper that raised him to the Brazilian national team, his pride in being runner-up in the world, his character and perseverance in the face of what he suffered after 1950, his humility and contribution to the formation of several archers where he passed, the friendships woven and the affectionate way he was treated, and his joy and gratitude for his career and life.

All of this is in direct opposition to both that memory and the image one has of Barbosa. It reveals to us how racist we still are. We owe him and all black men and women in Brazil other possibilities, other narratives, other images, under anti-racist perspectives. We need to understand not only the relationship between memory and history, but also between historical times, as well as our role as mediators of temporalities. It was in this direction that the Football Museum revised the Rito de Passagem room, removing the image of the centenary goalkeeper and presenting the following message: “Brazil’s defeat was unfairly attributed to Juvenal, Bigode and goalkeeper Barbosa — the three black players on the 1950s squad. Losing is part of the game. Racism, no.”

The collections collected in this research process are now available for consultation at the Brazilian Football Reference Center

References

ABRAHÃO, Bruno Otávio de Lacerda; SOARES, Antonio Jorge. O que o brasileiro não esquece nem a tiro é o chamado frango de Barbosa: questões sobre o racismo no futebol brasileiro. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 15, n. 2, p. 13-31, abr./jun. 2009.

ANTUNES, Fatima Martins Rodrigues Ferreira. Com brasileiro não há quem possa! Futebol e identidade em José Lins do Rego, Mário Filho e Nelson Rodrigues. São Paulo: Ed. da UNESP, 2004.

CAPOVILLA, Maurice. No país do futebol: a tragédia de 1950 e outras histórias (2010), por Luiz Carlos Barreto, Brasil, colorido; preto e branco, 16 min.

CORNELSEN, Elcio Loureiro. A memória do trauma de 1950 no testemunho do goleiro Barbosa. Esporte e Sociedade, Rio de Janeiro, v. 8, n. 21, mar. 2013.

FILHO, Mario. O negro no futebol brasileiro. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad, 2003.

FRANZINI, Fábio. Da expectativa fremente à decepção amarga: o Brasil e a Copa do Mundo de 1950. Revista de História, São Paulo, n. 163, p. 243-274, jul./dez. 2010.

FREITAS, Bruno. Queimando as traves de 50: glórias e castigo de Barbosa, maior goleiro da era romântica do futebol brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro, iVentura, 2013.

FURTADO, Jorge; AZEVEDO, Ana Luiza. 1988. Barbosa. Brasil, curta-metragem, colorido; preto e branco, 13 min.

GUILHERME, Paulo. Goleiros: heróis e anti-heróis da camisa 1. São Paulo, Alameda, 2006.

HALBWACHS, Maurice. A memória coletiva. São Paulo: Centauro, 2006.

HEIZER, Teixeira. Maracanazo: tragédias e epopeias de um estádio com alma. Rio de Janeiro, Mauad, 2010.

HOBSBAWM, Eric; RANGER, Terence. A invenção das tradições. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1997.

HOLLANDA, Bernardo Borges Buarque de. Genealogia da derrota: a reedição do livro O negro no futebol brasileiro e a construção do significado da Copa do Mundo de 1950 para o Brasil. Mosaico, Rio de Janeiro, v. 8, n. 12, p. 202-225, 2017.

JAL & GUAL. A história do futebol no Brasil através do cartum. Rio de Janeiro: Bom Texto, 2004.

LE GOFF, Jacques. História e memória. Campinas: Ed. da Unicamp, 2003.

MATTOS, Helvídio. 1994. A Copa de 1950. Brasil, colorido; preto e branco, 40 min.

MORAES NETO, Geneton. Dossiê 50: os onze jogadores revelam os segredos da maior tragédia do futebol brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2000.

MOURA, Gisella de Araújo. O Rio corre para o Maracanã. Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 1998.

MUYLAERT, Roberto. Barbosa: um gol faz cinqüenta anos. São Paulo: RMC, 2000.

NORA, Pierre. Entre memória e história: a problemática dos lugares. Projeto História, São Paulo, n. 10, p. 7-28, dez. 1993.

PERDIGÃO, Paulo. Anatomia de uma derrota. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 2000.

POLLAK, Michael. Memória, esquecimento, silêncio. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 2, n. 3, p. 3-15, 1989.

RICOUER, Paul. A memória, a história, o esquecimento. Campinas: Ed. da Unicamp, 2007.

RODRIGUES, Nelson. A pátria em chuteiras. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2013.

SIMON, Luís Augusto. Os 11 maiores goleiros do futebol brasileiro. São Paulo, Contexto, 2011.

VASCONCELLOS, Jorge. Recados da bola: doze depoimentos dos mestres do futebol brasileiro. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2010.

Marcel Diego Tonini

Senior researcher at the Brazilian Football Reference Center. Researcher of the temporary exhibition Time of Reaction — 100 years of goalkeeper Barbosa.